Preface to the Russian edition. Cecilia Sanders - Mother of Hospice

Cecilia Sanders - Hospice Mother

10 AUGUST 2015

EDITORIAL PORTAL "ORTHODOXY AND PEACE"

10 years ago, Cecilia Sanders, the founder of the modern hospice movement, died. She founded St Christopher's Hospice in London in 1967 and became the world's first modern hospice.

The first hospices

The very idea of caring for the terminally ill and dying was brought to Europe by Christianity. In antiquity, doctors believed that there was no need to help terminally ill people. Helping the hopelessly ill was considered an insult to the gods: after all, they had already passed a death sentence.

The first use of the word “hospice” in the sense of “a place for caring for the dying” appeared only in the 19th century. By this time, some medieval hospices had closed due to the Reformation. Others became nursing homes for elderly patients. Much of the work they previously did was taken over by "hospitals", where doctors only cared for patients who had a chance of recovery. The hopelessly ill lived out their days with virtually no medical care in nursing homes.

In the early nineteenth century, doctors rarely visited dying patients, even to pronounce their death. The priests did this.

"Ladies of Calvary"

The recent history of the hospice movement is associated with the name of Jeanne Garnier. A deeply religious Christian, she was widowed at age 24 and two of her children died. In 1842, Jeanne opened a shelter for terminally ill, dying women in her home in Lyon, sharing the last days of their lives with them, alleviating their suffering.

“I was sick and you visited Me” (Matthew 25:36)- this gospel phrase, spoken by Christ in a conversation with his disciples about the Judgment of God after the Second Coming and shortly before His Crucifixion, was written on the facade of Jeanne’s house. She named her shelter "Calvary".

Jeanne wanted the shelter to have an atmosphere of “respectful intimacy, prayer and calm in the face of death.” A year after the opening of the hospice, Jeanne died, writing shortly before her death: “I founded this shelter with an investment of 50 francs, and God’s Providence will finish what it started.”

And her work was continued by many: inspired by the example of Jeanne, the Frenchwoman Aurelia Jousset founded the second Calvary shelter in Paris in 1843, then the “Ladies of Calvary” went to other cities of France - Rouen, Marseille, Bordeaux, Saint-Etienne, then Brussels, and in 1899 - overseas, to New York. Modern palliative care for the dying is largely based on the principles laid down by the Ladies of Calvary.

Hospice "Ladies of Calvary". Saint Monica's Shelter. Late 19th century

"House of Saint Rose"

At the beginning of the 20th century, hospices began to open in London, New York, and Sydney, founded by ascetics of the Catholic and Anglican churches. At that time, most of the patients in hospices were dying from tuberculosis, which was incurable at that time, although there were also cancer patients.

Frances Davidson, the daughter of religious and wealthy parents from Aberdeen, founded the first "home for the dying" in London in 1885. There she met an Anglican priest, William Pennfeather. Together they created a “house of peace” for the poor dying of tuberculosis.

Rose Hawthorne, a wealthy and prosperous woman in the past, having buried her child and a close friend, became a nun of the Dominican order, “Mother Alphonse,” and founded the “House of St. Rose for the Incurable Ill” in Lower Manhattan. She and her associates called themselves “Ministers of Relief of Suffering from Incurable Cancer.”

"Hospice of the Mother of God"

The Irish nun of the Sisters of Charity, Maria Aikenhead, also devoted herself to serving the dying. Maria worked a lot in the order's hospitals and dreamed of creating a shelter for the dying, but a severe chronic illness forever confined her to her bed.

The convent in the poorest quarter of Dublin, where she spent her last years, after Mary's death, inspired by her faith and courage, her sisters in 1874 turned it into such an orphanage. The head of the “Hospice of the Mother of God” was the nun Maria Joanna.

Then other hospices were opened, including St. Joseph's Hospice in London at the beginning of the 20th century. It was to this hospice that Cecilia Sanders came, with whose name the newest page in the history of hospices in the world is associated.

St Joseph's Hospice. London

Face death with dignity

Cecilia graduated from Oxford University with a degree in social work. She went to work at St. Thomas's Hospital in London, where she met a refugee from Poland, David Tasma, who was dying of cancer. He refused to communicate with anyone. Only when Cecilia decided to tell David that he was dying did communication begin between them.

From David she learned very important things: what terrible pain a dying cancer patient experiences, how important it is to anesthetize him, giving him the opportunity to face death with dignity. After David's death, Cecilia converted to Christianity and decided to devote herself to caring for the dying.

In 951, she entered medical school, where she conducted research into the treatment of chronic pain syndrome. And in 1967, Cecilia organized the St. Christopher is the world's first modern hospice. It was Cecilia Sanders who introduced the concept of “total pain,” which includes physical, emotional, social and spiritual pain.

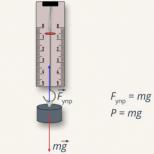

She constantly spoke about the need to combat “general pain” in incurable patients. “If pain is constant, then its control should be constant,” Sanders believed. By relieving a person, for example, of spiritual pain, the doctor alleviates general pain. But the unbearable pain that often leads to suicide in cancer patients is the main suffering; a person loses his dignity, his human appearance...

Photo: cicelysaundersinternational.org

Cecelia Sanders's major contribution to the hospice movement and to palliative medicine in general was her insistence on a strict regimen of morphine, not on demand, but by the hour. This regimen for dispensing pain medication was a revolutionary step in the care of terminally ill cancer patients. In other hospitals, doctors were afraid to give drugs to the dying - they say, they will become drug addicts...

St. Luke's Hospice patients experienced little to no physical pain. Hospice doctors used the so-called “Brompton cocktail”, consisting of opioids, cocaine and alcohol, to relieve pain.

Cecilia Sanders actively spread her ideas and received support all over the world: the hospice movement quickly spread to Europe and America. In 1979, for her services to her homeland, she was awarded the title Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

St Christopher's Hospice

On the 10th anniversary of Cecilia's death, her colleagues at St Christopher's Hospice met to remember Cecilia. Tom West, the hospice's former chief physician, remembers her this way:

“It all started 60 years ago... We studied together, went to the medical laboratory at St. Thomas's Hospital together. And then something happened that made us very close friends for life. Just before our final exams, my father was diagnosed with incurable lung cancer. And Cecilia moved in with us for three weeks.

She made these last three weeks of my father’s life not at all as terrible as we had feared. The therapists listened to her. And she established a strict order: “if there is pain, it needs to be relieved until it disappears completely,” “you need to give him a little whiskey,” “you need to help him empty his bowels.”

My father became the first terminal cancer patient whom Cecilia cared for at home.

Later she invited me to join the Christian Union, where I met two missionary doctors. They inspired me to travel to Nigeria, where I worked in a small missionary hospital. And Cecilia at this time in London created St. Hospice. Christopher. She wrote to me often and told me how the case was going.

One day, after selling a terribly expensive Persian carpet, she bought a ticket and visited me in Nigeria. I examined everything - including the maternity ward, which was built and equipped with money from the Guild of Goldsmiths, with whom she introduced me.

Cecilia suggested that I become the chief physician of a hospice, which I did after returning from Nigeria. The next 20 years were exceptionally eventful...We truly “practiced it and preached it.”

...I have already retired, years have passed. And just a few weeks before Cecilia died, a miracle happened - I called the hospice, and she answered the phone. She no longer got out of bed, becoming a patient of her own hospice.

Quietly, calmly, we said the farewell phrases accepted in our hospice: “Forgive me. Thank you for everything. Goodbye".

Cecilia Sanders died of cancer at St Christopher's Hospice, aged 87, in 2005.

Photo: BBC

10 Commandments of Hospice

The practical experience of foreign and domestic hospices made it possible to develop a number of rules, regulations, and moral precepts, first summarized and formulated in the form of 10 commandments by psychiatrist Andrei Gnezdilov. Subsequently, the doctor, founder and chief physician of the First Moscow Hospice, Vera Millionshchikova, made additions to the text of the commandments. In expanded form, the text of the commandments looks like this:

1. Hospice is not a house of death. It's a life worth living to the end. We work with real people. Only they die before us.

2. The main idea of hospice is to relieve pain and suffering, both physical and mental. We can do little on our own, and only together with the patient and his loved ones do we find enormous strength and opportunities.

3. You cannot rush death and you cannot slow down death. Each person lives his own life. Nobody knows its time. We are only fellow travelers at this stage of the patient's life.

4. You can’t pay for death, just like you can’t pay for birth.

5. If a patient cannot be cured, this does not mean that nothing can be done for him. What seems like a small thing, a trifle in the life of a healthy person, has great meaning for the patient.

6. The patient and his relatives are a single whole. Be gentle when entering the family. Don't judge, but help.

7. The patient is closer to death, therefore he is wise, behold his wisdom.

8. Each person is individual. You cannot impose your beliefs on the patient. The patient gives us more than we can give him.

9. The hospice's reputation is your reputation.

10. Take your time when visiting the patient. Don't stand over the patient - sit next to him. No matter how little time there is, it is enough to do everything possible. If you think that you didn’t manage to do everything, then communicating with the loved ones of the deceased will calm you down.

11. You must accept everything from the patient, even aggression. Before you do anything, understand the person; before you understand, accept him.

12. Tell the truth if the patient wishes it and if he is ready for it. Always be prepared for truth and sincerity, but do not rush.

13. An “unplanned” visit is no less valuable than a “scheduled” visit. Visit the patient often. If you can't come in, call; If you can’t call, remember and still... call.

14. Hospice is a home for patients. We are the owners of this house, so: change your shoes and wash your cup.

15. Do not leave your kindness, honesty and sincerity with the patient - always carry them with you.

16. The main thing is that you should know that you know very little.

When writing the material, books by V.S. were used. Luchkevich, G.L. Mikirtichan, R.V. Suvorova, V.V. Shepilov “Problems of medical ethics in surgery” and Clark, David, and Jane Seymour. Reflections on Palliative Care.

Translation Anna Barabash

http://www.pravmir.ru/sesiliya-sanders-mat-hospisov/

In 1947, Dr. Cecilia Sanders, then a newly certified social worker and former nurse, met on her first round at St. Luke is a patient in his forties, a pilot named David Tasma, who came from Poland. He had inoperable cancer. After several months, he was transferred to another hospital, where Dr. Sanders visited him for two more months before his death. They talked a lot about what could help him live the rest of his life with dignity, about how, by freeing a dying person from pain, give him the opportunity to reconcile with himself and find the meaning of his life and death. These conversations laid the foundation for the philosophy of the modern hospice movement.

After the death of David Tasma, Cecilia Sanders became convinced that a new type of hospice needed to be created, giving patients the freedom to find their own path to meaning. The hospice philosophy was based on openness to diverse experiences, scientific rigor and concern for the individual.

After St Christopher's Hospice, the first modern hospice created through the efforts of Cecilia Sanders, opened its inpatient hospital in the UK in 1967 and organized a visiting service in 1969, a delegation from North America arrived there. Florence Wald, dean of the school of nursing at Yele, and Edd Dobingel, chaplain of the University Hospital, were among the founders of the first mobile hospice service in the city. New Haven, Connecticut. In 1975, a hospice appeared in Canada, in Montreal. This hospice was based on a very modest palliative care unit and included a visiting service as well as a number of consultant doctors. This was the first use of the word "palliative" in this area, since in French-speaking Canada the word hospice meant care or inadequate care.

The teams at all these hospices developed the principles, now supported by the World Health Organization, that palliative medicine:

· Affirms life and views death as a normal process;

· Does not speed up or slow down death;

· Provides relief from pain and other bothersome symptoms;

· Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care;

· Offers a support system to help patients live an active life to the end;

· Offers a support system to help families cope during a relative's illness and after the death.

The first hospices in England, such as St Christopher's Hospice and Helen House children's hospice, were set up in special homes. These are private hospices, they are completely independent and separate from hospitals. Along with this, the English National Cancer Society is creating hospices on the territory of existing hospitals, where they can use everything that the clinics have.

Traditionally, hospices in the UK are organized in specially built buildings. At the same time, children's hospices organize a significant part of their work for families in their care at home, because they help families raising children with various diseases and varying life expectancies. The main criterion is that the child is not destined to become an adult. In this building itself, a family with a sick child or one child can spend an average of 1-2 weeks a year so that relatives can relax. It is typical that children with cancer are very rarely cared for by hospices organized in this way.

A terminally ill person is a child on the contrary. If children are weak at first, but learn everything with age, then a dying adult gradually loses acquired functions and often feels pain and fear of death. Making the life of a dying patient easier is the goal of palliative care. Its main principle is an integrated approach: not only patient care is important, but also the emotional state of the patient and his family. Hospice is one of the tools of palliative care that helps make the end-of-life process as painless—in every sense—as possible.

From religion to medicine

Palliative care is always accompanied by social support measures: help from a social worker, registration of disability, and receipt of medications. The philosophy of palliative care is to ensure the right to life until the very last days.

The need for a decent “life for the rest of your life” came to medical culture relatively recently. In Antiquity, such an approach was not accepted, and the very idea of helping the hopelessly ill began to spread in Europe only with the advent of Christianity.

The very concept of “hospice” originally meant “stranger” and only in the 19th century acquired its current meaning. The predecessor of hospices was the shelter of Christian Fabiola, a Roman matron, disciple of St. Jerome and traveler. In her home, she received all the suffering - from pilgrims to the Holy Land to destitute beggars - where she looked after the guests along with her like-minded women.

Later, already in the Middle Ages, similar shelters began to appear in many monasteries. For centuries, death was closer to religion than to medicine: the role of the last one to help the sick was often taken on by a priest rather than a doctor.

Hospices only became associated with end-of-life care in the 19th century. By this time, some of the monasteries, and with them the orphanages, were closed due to the Reformation. The rest turned into nursing homes for the infirm elderly. The terminally ill found themselves in the care of hospitals, where they valued the life of someone who could still recover more than the comfort of an already doomed patient.

After a long decline, hospice as a word and as a phenomenon is being revived in France. Subsequent charitable work was again done by women: Jeanne Garnier, a young Christian woman, turned her home into a hospice for the dying in 1842, calling it “Calvary.” Later, Jeanne’s associates opened several more hospices throughout the country - some of them still operate in France.

Around the same time, the first hospices appeared in Dublin, and then, at the beginning of the 20th century, they opened in England, the USA and Australia.

Cecelia Sanders Photo: Cely Saunders Archive

Cecilia Sanders' Common Pain

In 1948, Cecilia Sanders, an Oxford graduate with a degree in social work, attended the first round of St. Luke's Home for the Poor Dying. She met David Tasma there, who had no chance of recovery: inoperable cancer. Her friendship with a terminally ill patient gave Sanders a powerful understanding of the pain and fear experienced by those whose lives are ending.

Sanders realized that it was necessary to give the patient freedom from physical and spiritual suffering - this respite was necessary for him in order to come to terms with his impending death. She later received her medical training and devoted several years to research into chronic pain syndrome. Sanders formulated the concept of “general pain,” which means not only physical illness, but also social, spiritual and emotional pain. Thus, according to her findings, when a doctor provides a patient with pain medications, he makes other aspects of his life easier. Cecilia Sanders's contribution to palliative medicine is difficult to overestimate: she was the first to insist on a clear schedule for the administration of morphine. Before her, doctors were afraid to regularly anesthetize a patient.

In 1967, Sanders opened her own hospice in London in the modern sense, giving it the name of the martyr, St. Christopher. In 1969, the first mobile service appeared there. In the 70s, the first hospices opened in Canada, and in the 80s, the ideas of Sanders and the hospice movement spread throughout the world.

From England to Russia

Almshouses and hospices with a few beds for the terminally ill have existed in Russia for a long time and without reference to the word “hospice”. The philosophy of palliative care came here in the early 90s with journalist Victor Zorza and his wife Rosemary, whose daughter died of melanoma. The couple wrote the book “The Path to Death. Life to the end,” where they talked about their daughter’s last months in a hospice.

“I don’t want to die,” our daughter Jane said when she learned at age twenty-five that she had cancer. She lived only a few months and proved that when dying, it is not necessary to experience the horror that our imagination depicts. Death is usually considered a defeat, but Jane's death was a victory of sorts—a battle won against pain and fear. Jane shared her triumph with those who helped her in this. This became possible thanks to the new British approach to caring for the dying.

Jane's parents promised to spread the hospice philosophy throughout the world. In Russia, they were lucky to meet Andrei Gnezdilov, a psychiatrist, with whom the first Russian hospice was opened in the St. Petersburg village of Lakhta in 1990. The motto of this place was the phrase: “If it is impossible to add days to life, add life to days.”

A little later, the Russian-British Hospice Association was created in Moscow to provide professional support to Russian palliative care institutions. The next domestic hospice appeared in 1991 in the Tula region, and in 1992-1994, hospices opened in Arkhangelsk, Tyumen, Yaroslavl, Dimitrovgrad and Ulyanovsk.

Since 1992, a mobile team of volunteers began working in the capital to help the dying at home. In 1994, Vera Vasilyevna Millionshchikova, an oncologist, whom Victor Zorza met back in the early 90s, became its leader.

According to colleagues, the principles of palliative care were close to Vera Vasilyevna before: she led her patients to the end, without leaving them alone with the destructive symptoms of the disease. Thanks to her efforts and the help of Victor Zorza, who turned to Yuri Luzhkov with a letter from Margaret Thatcher, in 1997, the First Moscow Hospice inpatient facility was opened on Dovator Street, later named after Millionshchikova.

The structure of palliative care today is quite simple: it is either a hospital, or visiting visiting services and palliative rooms (though there are no rooms for children). Inpatient settings include hospice, hospital palliative care, or licensed nursing units. There are few of the latter in Russia - about a thousand.

Photo: Yegor Aleyev/TASS

Photo: Yegor Aleyev/TASS

No one has to suffer: towards popularization through social projects

“If a person cannot be cured, this does not mean that he cannot be helped,” says the Vera Hospice Fund, which appeared in 2006, when Millionshchikova herself became seriously ill. Today the Foundation helps not only the First Moscow Hospice, but also regional palliative institutions. With the support of the Foundation, there is a “House with a Lighthouse” in Moscow, the only children’s hospice in the capital.

“Vera”, “AdVita”, “Gift of Life”, “Line of Life”, “Children’s Palliative” and other non-governmental associations aimed at solving the problems of seriously ill children and adults arose in Russia along with the development of a culture of private charity and the popularization of palliative care. The “Association of Professional Participants in Hospice Care” holds annual conferences where specialists in various fields can exchange experiences with Russian and foreign colleagues, and in some clinics and hospitals “patient schools” are being developed: information about caring for patients in the terminal stage becomes more accessible. True, it is still not easy to talk about death widely. Today, not only NGOs, but also large commercial companies use their own capital, name and influence to attract public attention to the problems of palliative patients.

To talk about the tasks of palliative care and new medical technologies that can make life easier for patients and their loved ones, in 2016 the pharmaceutical company Takeda launched a large-scale social project “Takeda. Pain and Will." The emotional language of this project is sports and art: it included exhibitions of contemporary artists in Moscow and St. Petersburg and the “Faster than Pain” campaign at the Moscow half-marathons of the “Thunder” series. Through visual art, artists tried to understand the experiences of suffering at various stages of life, and participants in the race donated funds for people who have to cope with pain every day. As part of “Faster than Pain”, it was possible to raise funds to support hospices in Krasnodar, Novosibirsk and Yekaterinburg.

In November, the competition among student artists “Takeda. ART/HELP. Overcoming”, and in the spring of 2018, as part of the exchange year of culture between Russia and Japan, a joint exhibition of young Russian and Japanese authors will be held. The theme is still the same - overcoming: the works, some of which were created specifically for the competition, are dedicated to the confrontation between a person and an illness, internal and external resources that help a dying person endure fear and pain.

“Many works were created specifically for our competition, and the annotations to the works sent by the authors speak about how important and relevant the tasks of palliative medicine are in modern society,” notes Andrey Potapov, CEO of Takeda Russia, head of the CIS region .

Today, new technologies in medicine help solve problems that were previously considered insoluble. New types of non-invasive pain relief are emerging, targeted therapy is increasingly developing, capable of coping with the most complex tasks - helping with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and inflammatory bowel diseases. At the same time, no technology can replace care and attention to the patient - the principles on which patient care in palliative care facilities is based.

Photo: Valery Sharifulin/TASS

Photo: Valery Sharifulin/TASS

"Additional era"

It is worth understanding: a hospice is not a house of death, but a place where you are happy every day and do not put anything off until tomorrow. Doctors are confident that high-quality palliative care can change the attitude of Russians towards healthcare. “We often hear words like “we were abandoned,” “we were thrown out of the hospital” from people whose relatives left home in terrible stress,” says Diana Nevzorova, deputy director at the Moscow Multidisciplinary Center for Palliative Care of the Department of Health. “All because the general practitioner did not refer them to palliative care and did not make life easier for the patient and relatives. It may be different. There is no palliative culture in the medical system yet, but it is developing.”

Since 2011, federal law has made it possible for palliative medicine to exist as a separate type of medical care. There are now almost 10,000 beds in the country that are licensed for palliative care. New beds are opening very quickly: over the past two years their number has increased by almost a third. True, growth is associated with insufficient professionalism: people start working without experience in this field.

The distinction between conventional medicine and palliative care is due to the fact that such care is a new phenomenon for the medical education system. Many doctors simply do not know that it is possible to transfer the patient further, and hospices and hospitals often do not maintain direct contact. Now one of the main tasks of palliative care specialists is the implementation of educational programs in medical universities, training of qualified specialists and training of already working doctors.

Problems also include a low number of outreach services and the need for new types of painkillers. For the latter, according to Diana Nevzorova, the Ministry of Health is not at all ready. At the same time, bedridden and long-sick patients become very tired of injections: pain relief in the form of tablets or special patches will make their life more comfortable and reduce stress levels.

Photo: Valery Sharifulin/TASS

Photo: Valery Sharifulin/TASS

Children and adults

“We cannot clearly understand when the dying process begins. But an elderly person, for example, with a chronic destructive disease, who is now in a severe stage - this is dying? Of course, we say that we are fighting victoriously and providing specialized assistance. Yes, we provide it, but we understand that it is not in our power to cure the patient. No matter what we say about healthcare, death all over the world is one hundred percent,” explains Diana Nevzorova.

This is something that everyone seems to need to learn. And this doesn’t seem to be scary, because it’s logical and correct, but it’s still not easy to come to terms with the idea that children die too.

The fundamental difference between pediatric and adult palliative medicine lies in the diagnoses. According to statistics, in children's palliative care there is only 6% oncology, the rest is genetic mutations, developmental defects and neurology. Among adults, the majority are people with cardiovascular diseases, cancer patients and, in general, geriatric (i.e. elderly and senile) patients.

A common problem for children and adults is the exclusion of relatives. Palliative care promotes 24-hour visiting hours, but some facilities still limit the hours for guests. In addition, children's palliative beds are often opened in intensive care units: it turns out that a child in intensive care and a palliative patient are lying next to each other. How to decide who to let your mother see and who not to let? In Russia, there has been talk for a long time about open resuscitation, but the conditions for it have not yet been prepared.

Today there are about 100 hospices operating in Russia. This is a very small figure, which does not meet the requirements of the World Health Organization: in reality, there should be one hospice for every 400 thousand people. This means that we need to build another 250, provide reliable outpatient services in each and build a staff of professional specialists. One way or another, palliative care should become a well-functioning part of healthcare - it is integrally linked to human rights, and everyone, as we remember, has the right to life and the highest attainable standard of health.

The material was prepared with the participation of Diana Nevzorova, deputy. director at M Oscow multidisciplinary palliative care center DZM.

2. Hospice movement today

In 1947, Dr. Cecilia Sanders, then a newly certified social worker and former nurse, met on her first round at St. Luke is a patient in his forties, a pilot named David Tasma, who came from Poland. He had inoperable cancer. After several months, he was transferred to another hospital, where Dr. Sanders visited him for two more months before his death. They talked a lot about what could help him live the rest of his life with dignity, about how, by freeing a dying person from pain, give him the opportunity to reconcile with himself and find the meaning of his life and death. These conversations laid the foundation for the philosophy of the modern hospice movement.

After the death of David Tasma, Cecilia Sanders became convinced that a new type of hospice needed to be created, giving patients the freedom to find their own path to meaning. The hospice philosophy was based on openness to diverse experiences, scientific rigor and concern for the individual.

After St Christopher's Hospice, the first modern hospice created through the efforts of Cecilia Sanders, opened its inpatient hospital in the UK in 1967 and organized a visiting service in 1969, a delegation from North America arrived there. Florence Wald, dean of the school of nursing at Yele, and Edd Dobingel, chaplain of the University Hospital, were among the founders of the first mobile hospice service in the city. New Haven, Connecticut. In 1975, a hospice appeared in Canada, in Montreal. This hospice was based on a very modest palliative care unit and included a visiting service as well as a number of consultant doctors. This was the first use of the word "palliative" in this area, since in French-speaking Canada the word hospice meant care or inadequate care.

The teams at all these hospices developed the principles, now supported by the World Health Organization, that palliative medicine:

· Affirms life and views death as a normal process;

· Does not speed up or slow down death;

· Provides relief from pain and other bothersome symptoms;

· Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care;

· Offers a support system to help patients live an active life to the end;

· Offers a support system to help families cope during a relative's illness and after the death.

The first hospices in England, such as St Christopher's Hospice and Helen House children's hospice, were set up in special homes. These are private hospices, they are completely independent and separate from hospitals. Along with this, the English National Cancer Society is creating hospices on the territory of existing hospitals, where they can use everything that the clinics have.

Traditionally, hospices in the UK are organized in specially built buildings. At the same time, children's hospices organize a significant part of their work for families in their care at home, because they help families raising children with various diseases and varying life expectancies. The main criterion is that the child is not destined to become an adult. In this building itself, a family with a sick child or one child can spend an average of 1-2 weeks a year so that relatives can relax. It is typical that children with cancer are very rarely cared for by hospices organized in this way.

Since the early 1980s, the ideas of the hospice movement have begun to spread throughout the world. Since 1977, the Information Center has been operating at the St. Christopher Hospice, which promotes the ideology of the hospice movement, helps newly created hospices and volunteer groups with literature and practical recommendations for organizing day hospitals and outreach services. Regular conferences on hospice care allow doctors, nurses and volunteers from different religions and cultures to meet and exchange experiences. Very often, it was at such conferences that a decision arose to create a hospice in a particular country, as was the case at the sixth international conference, when the head nurse of a clinic in Lagos wrote an appeal to the Minister of Health of Nigeria with a request to facilitate the organization of a hospice in Nairobi.

In some countries, the hospice movement developed in this way, while in others, hospices were formed on the basis of more traditional medical institutions. Like in India, where statistics show that out of a population of 900 million, one in eight people gets cancer, and 80 percent seek treatment when it is too late. In 1980, Dr. de Souza, head of a department at a large hospital in Bombay, spoke at the First International Conference on Hospice Care. He spoke very convincingly about the problems of the hospice movement in developing countries, about hunger and poverty, as well as physical pain. “It’s bad enough in itself to be old and frail. But to be old, sick in the last stage of cancer, hungry and poor, and not have loved ones to take care of you, is probably the height of human suffering.” Thanks to Dr. de Souza, the first hospice opened in Bombay in 1986, and then another. Sisters from the Order of the Holy Cross, who received special medical education, took care of the patients. In November 1991, India celebrated the 5th anniversary of the founding of the first hospice, in honor of which the international conference “Sharing Experience: East Meets West” was held in India.

In 1972, in Poland, one of the first among socialist countries, the first hospice appeared in Krakow. By the end of the eighties, when the Palliative Medicine Clinic at the Academy of Medical Sciences was created, palliative care became part of the structures of public health services. There are currently about 50 hospices in Poland, both secular and church-owned.

In Russia, the first hospice appeared in 1990 in St. Petersburg on the initiative of Victor Zorza, an English journalist and active participant in the hospice movement. He and his wife, Rosemary, wrote the book “The Story of Jane Zorza”; it has two subtitles: “The Path to Death” and “Living to the End.” The book was translated into Russian and published by the Progress publishing house in 1990. V. Zorza brought to Moscow and then to Leningrad not only the book, but also a great desire to contribute to the development of the Hospice movement in Russia. This was his promise to his daughter Jane, who received enormous help and support in the last days of her life in one of the hospices in England.

Andrei Vladimirovich Gnezdilov became the director of the first hospice. After some time, the Russian-British Hospice Association was created in Moscow to provide professional support to Russian hospices.

In the early 90s, the Board of Trustees for the creation of Hospices in the USSR was created, the chairman of which was Academician D.S. Likhachev. A home hospice for children with cancer was organized in Moscow on the initiative of E.I. Moiseenko, an employee of the Research Institute of Children's Oncology and Hematology, in October 1993 as one of the areas of work of the Children's Section of the Moscow Society for Helping Cancer Patients. The first hospices for adult patients began to be created in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other cities of Russia

In 1992, a small group of volunteers and medical workers was organized in Moscow to help terminally ill patients at home. In 1997, with the financial and administrative support of the Moscow government, a new building for the First Moscow Hospice was opened in the city center, on Dovator Street.

The ideas of the hospice movement continue to spread throughout Russia. In total, there are now about 20 hospices in Russia, including in Kazan, Ulyanovsk, Yaroslavl and other cities.

In the United States, the hospice system is extremely diverse. They differ in the amount of assistance provided, structure and organization, including sources of funding. Children's Hospice in Norfolk, Virginia, provides assistance to all families of this relatively small city who have children with serious illnesses. These include children with sublethal hereditary and congenital diseases, and children with heart defects, asthma, and cancer, including those who have been cured. Only children with HIV infection are not included in this group; they are helped by a special organization. The main form of organization of assistance in such conditions is home assistance. If a child requires inpatient care due to the severity of his condition or for social reasons, he is hospitalized in a hospital.

However, the widespread use of hospices is only “one side of the coin.” Despite the apparent external well-being, not all of the problems of the hospice movement have been resolved. In particular, the President of the American Hospice Association notes with regret that over the 25 years of the existence of American hospices, many employees have not been able to understand the essence of hospice ideology. In addition, in his opinion, hospices need to be more active and influence public opinion, otherwise they (i.e., hospices) may find themselves “hostage to the whims of health authorities.” You can become a patient of an American hospice only if you have sufficiently large medical insurance. In the United States, cancer patients make up 80% of hospice patients, and only 20% are neurological and HIV-infected patients.

The Berlin hospice has only 12 beds. But since the standard of living there is much higher, the Germans, if necessary, can “organize an intensive care unit with highly qualified medical staff at home.”

Hospices bring economic benefits to any state, be it the USA, Germany or Ukraine. And quite a lot. Americans evaluate the economic feasibility of hospices by the value of the gross national product produced by relatives freed from caring for the terminally ill. In many countries, hospices are widely used for end-stage AIDS patients, which are significantly cheaper to operate than conventional hospitals. Positive experience in using hospices for the care and treatment of AIDS patients has been accumulated in the USA, Canada, Great Britain, the Netherlands and other countries. In particular, at the end of June 2003, the third hospice was opened in Philadelphia (USA), belonging to the Calcutta House system, where patients will be in separate rooms with individual toilets and baths; a kitchen, laundry, dining room, living room and meditation room are common to all hospice residents. Many patients, entering such hospices, “start a new life” - the conditions here are so much better than their previous way of life. In recent years, computer courses have become very popular among hospice residents; after completing them, patients acquire new specialties and even begin to provide financial assistance to their hospices.

Many years of experience in a children's oncology clinic shows that if parents of a terminally ill child in the terminal stage of a tumor process are given the right to choose - to leave him in the clinic until the end, or to take the child home, most of them choose the second option.

The ideology of the organizers of the Moscow Children's Hospice at home for cancer patients is that the dying and death of a terminally ill child should take place at home, in the only place where every moment of the last and most tragic days of his life he can be surrounded by the warmth of home, those close to him and understanding him, the people who love him, in the world of his childhood dreams and fantasies.

It is obvious that all his loved ones suffer along with the child, so not only the child himself, but also his entire family needs love and support.

Organizing assistance to a family caring for a seriously ill child at home assumes that the maximum possible pain relief and solving other care tasks, as well as assistance in solving psychological and social problems, are provided by specialists from various disciplines: doctors, nurses, social workers, psychologists, priests, volunteers (volunteers) who have undergone special training. An individualized care program is tailored to meet the specific needs of each patient and family. Support for loved ones continues after the death of a child for as long as they need it.

Bibliography

1. Byalik M.A. Consultations on pediatric oncology. – M.: Doctor, 2003.

2. Great Medical Encyclopedia. T.21. / Ed. B.V. Petrovsky. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1983.

3. Ledyaeva M. Philosophy of pain. // Janitor, No. 5. – 2001.

4. Lvova L.V. Responsibility to the dying. – M.: Vlados, 2003.

5. Lexikon des Sozial- und Gesundhetswesens.//Hggb. Dr. R. Bauer., Oldenbourg Verlag, Muenchen-Wien, 1992.

6. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Ed. By D. Doyle, G.W. Hanks, N. MacDonald. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1995.

are stated, and the goal of the staff is to alleviate patients’ physical and mental suffering in anticipation of departure to another world. 1. Organization of activities of hospice-type institutions in Russia 1.1 History of the creation of hospices The word “hospice” has Latin roots and literally means shelter, almshouse. During the era of the Crusades, monasteries arose along the route of the Crusaders, which...

They turn to unconventional methods of treatment - in this case, hospice social workers are required to give a classical description of these methods and be able to distinguish quackery from them. One of the most important tasks of social work in a hospice is helping the relatives of patients. Relatives, during the period of illness of a loved one, go through all the same stages as the patient - starting from denial, reluctance...

During his life, he takes on some of the problems and thereby turns into an object of care for the social service. Purpose of the work: analysis of social and medical work with people suffering from cancer. 1. Rehabilitation of cancer patients Medical care in industrialized countries with highly developed healthcare systems is divided into preventive, curative and...

Horned, humanoid monsters, thus showing a tendency towards aggressive behavior. Consequently, having analyzed the results of an empirical study of the level of tolerance in children of primary school age, we found that tolerance is not sufficiently developed; difficulties were caused by questions related to the definition of such concepts as “me”, “me and others”, “patience” and “tolerance” , What...